One of my friends called me last night. He had checked himself into the hospital because of his bipolar disease. He told the physicians he had the Borna virus and it was flaring up. We had used frequency transmission to deal with it on multiple occasions. The hospital physicians asked, “What’s the Borna virus?” They then proceeded to give him too much Lithium resulting in a two week hospital stay.

Ignorance masquerading as science is pseudoscience and medical error is the third leading cause of death, mostly based on “scientists” who are supposed to know what they are doing. When they used to do autopsies in real medicine to find out what was going on, physicians in the U.S. and the U.K. discovered a third of the patients that died in hospitals died of an undiagnosed disease. So they have pretty much stopped doing autopsies as it puts them at risk of being sued for malpractice.

If my friends physicians consulted PubMed they would have found over 862 papers in the medical journals on the borna virus. It is associated with a wide variety of mental illness, particularly bipolar disease and depression.

Why didn’t the physicians consult his medical records at his primary physician’s office? They would have found out that he had tested positive for the borna virus and the primary physician was handling it, including the appropriate does of lithium. This failure to review available medical information on a patient will be viewed as malpractice in the not too distant future. There is a national initiative to enable sharing of this critical patient care information. While we are waiting for computer systems to do it automatically, how about using an old fashion phone call?

The physicians should have immediately queried the internet about the patient’s problem. Every bipolar person I have ever tested has it, and so do most members of the family. The virus is very widespread and causes all kinds of problems in addition to bipolar disease.

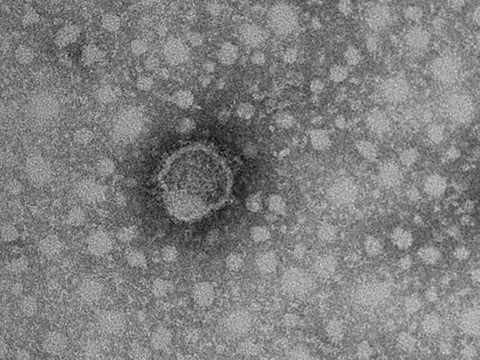

They wanted to know how he caught it. They could have done a Google search on “borna virus.” They would have found that 8% of our DNA is actually borna virus DNA. Or they might read a comprehensive review of the borna virus from the National Institutes of Health We used to teach science in medical schools. I wonder what they are teaching students these days?

The effects of Borna virus were first noticed in Saxony in Germany in 1766 in horses – first they got sad, and then hyperactive, and then most of them died. But the virus got its name about a century ago, when it killed some 2,000 cavalry horses in the town of Borna in Germany. But only recently, in the 1990s, have we found a link between this virus and depression. Depression is a disorder of your mood or emotions. It affects some 5% of the population at any given time. There’s actually a bunch of diseases that go under the single name of “depression”, and they tend to come and go during your life. They do more than just make you a little bit unhappy. They can cause severe disability, greater than is caused by heart disease, diabetes or even arthritis. In fact, it’s thought that 70% of suicides happen in people suffering from depression. But what’s the evidence that this strange new virus called Borna virus can cause depression?

Well, much of this research has been done by two virologists, Hanns Ludwig from the Free University of Berlin, and Liv Bode from the Robert Koch Institute (also in Berlin). In 1994, they found that clinically depressed people were more likely to have some of the proteins associated with Borna virus in their blood. The next year, they found traces of the actual RNA of the Borna virus as well. In 1996, these virologists took some Borna virus from clinically depressed patients, and when they injected this Borna virus into rabbits, the rabbits became apathetic, sluggish, withdrawn and stopped their normal grooming – in other words, the rabbits started suffering depression. And in January 1997, they found that if they used the anti-virus drug amantadine in depressed patients, as the virus disappeared from the blood stream, so did the symptoms of depression.

When I was teaching medical students at the University of Colorado Medical School from 1975-1983, we did not go home with a question like this unanswered. And we had to do real work in the medical library to get the answer. Today it takes three minutes on the internet.

The current issue of Health Affairs discusses the appalling 17 year gap between evidence based findings in the leading medical journals and information that is resident in the typical physicians head:

Health Affairs, Vol 24, Issue 1, 151-162

Copyright © 2005 by Project HOPE

DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.151

Implementing Evidence |

Evidence-Based Decision Making: Global Evidence, Local Decisions

Carolyn M. Clancy and Kelly Cronin

Despite the notable progress to date, evidence-based decision making has been largely overshadowed by the persistence of poor-quality care in the United States. Elizabeth McGlynn’s landmark report on U.S. health care quality, AHRQ’s National Healthcare Quality Report, and a recent cross-national report on quality indicators raise important questions about the gap between the promise of evidence-based health care and its current level of adoption. All stakeholders in the health care system presumably find the current seventeen-year delay from evidence to practice unacceptable. This translation chasm is even more intolerable, given the increased array of choices resulting from large public and private investments in biomedical science. Although many factors, including local professional norms and patients’ values and preferences, contribute to deviations from evidence-based care, a fundamental question remains: Why does the gap persist?

Limited resources. Investments in biomedical science have resulted in a wide variety of diagnostic and therapeutic options for clinicians and patients. The extant infrastructure for conducting systematic reviews–including AHRQ’s Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs), the worldwide Cochrane Collaboration, and independent private-sector organizations–has led to much progress in developing methods and conceptual enhancements for systematic reviews. Nevertheless, the field is not advancing as rapidly as it could because of limited resources.

Knowledge chasm. Moreover, by definition, systematic reviews rely on available studies. Since the link between decisionmakers’ needs and establishment of clinical research priorities is somewhat circuitous, the net result is that decision-makers have few resources for learning quickly which patients are likely to benefit from new options and which patients will experience marginal benefits or outright harm. Payers and consumers confront the same knowledge chasm and lack good information for coverage decisions, cost sharing, and treatment choices.

Need for a systems approach. We now know that knowledge about best practice is necessary but not sufficient to effect change in practice and policy. Impatient purchasers are testing innovations to identify incentives and programs that reward evidence-based (“best”) practice, but they have a limited knowledge base on which to derive or evaluate new approaches. Although the Institute of Medicine’s reports on medical errors and quality have reinforced the importance of a systems approach to improvement, major support for research to inform such an approach has only recently become available.

Poor accessibility. Finally, evidence is infrequently available in a form that can be acted upon at the time decisions must be made. From clinical encounters to policy decisions, there are few clear pathways between the evidence that is available through peer-reviewed literature reviews and the point of decision making. Clinicians searching for information all too often find that existing knowledge is not accessible in real time and may not necessarily map to the issue at hand. Also, although consumers are increasingly active in seeking information about health and specific conditions, most of this activity is peripheral to care delivery. Personalized decision making, including provider and treatment selection as well as self-management, looms on the horizon. Development and adoption of personal health records could support individual choice based on current information.